William Byrd (c.1540-1623)

[Commonly used but doubtful portrait of 1729]

William Byrd - Ne irascaris, Domine

William Byrd is often considered the greatest English composer of the Renaissance period. He was probably born in London in 1540, possibly in the parish of All Hallows Lombard Street, where his parents are thought to have lived. There is evidence that he studied with Thomas Tallis at some point in his early years , but his first known appointment was as organist and choirmaster of Lincoln Cathedral, where he stayed until 1572. By then he was an established figure, becoming in this year (following Tallis) a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal, that is, someone who performed in church services for the sovereign. Three years later, he and Tallis were granted a patent to print and sell music, with a monopoly of polyphonic music. Those privileges were all the more significant as he was a Roman Catholic for most of his adult life, in an aggressively Protestant England. He even had his salary at Lincoln docked for a time, possibly for some religious infringement. In fact he and his wife Julian, whom he married in 1568, were recusants – people who refused to attend Anglican services, which were compulsory. He nevertheless enjoyed the favour of Queen Elizabeth, perhaps helped by the fact that she was a music lover and keyboard player. Just as well, as this was a time when Catholics were being persecuted and even executed for their beliefs. Byrd was a Catholic by conviction, not by birth – the only Catholic in the Byrd family. It is not clear exactly when he converted; his recorded association with Catholicism began in the 1570s.

He was unusual among polyphonic composers in leaving a considerable legacy of instrumental music, for consorts and keyboard. (His sister Barbara married Robert Broughe, a maker of organs and virginals.) Byrd was not as prolific as say Lassus or Palestrina, but he left over 400 works in all. It is for his innovation, passion and originality that his sacred music is known. As Brett, one of his biographers, has said , he “completely assimilated continental techniques, but he also strove to preserve various advantageous elements of insularity – particularly the rhapsodic sense of melody cultivated by his predecessors”. (Listen to Ne irascaris domine (Be not angry O Lord) , one of Byrd’s most moving settings, if you wish to hear this – you can practically hum the melodies.) He tells us about his inspiration by religious texts: he wrote in the preface to one of his collections of Gradualia, 'In the very sentences … there is such hidden and concealed power that to a man thinking about divine things and turning them over attentively and earnestly in his mind, the most appropriate measures come, I know not how, as if by their own free will…'

What to listen for: Byrd’s music is perhaps the most sophisticated of any English composer from this era. The elegance of the imitation between the voice parts (where melodies are passed from voice to voice) is combined with a deeply skilful use of homophony (where all the voices sing the same rhythm at the same time), often to underscore words of particular importance. In addition, the way that Byrd sets text, with the attention of expressing their meaning, represents something of a high point. In the video above, and in particular the words ‘Sion deserta facta est, Jerusalem desolata est’ (Sion has been made a desert, Jerusalem is desolate), Byrd finds a musical language of deep despair in order to bring the text to life.

He wrote both for the Church of England on English texts, but also a great deal in Latin, much of which had to be performed privately. There was a celebrated exchange with the Catholic composer Philippe de Monte, who sent him his setting of the beginning of Psalm 137, Super flumina Babylonis (By the waters of Babylon) . Byrd sent him back his own setting of the remainder of the Psalm, Quomodo cantabimus (How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?) Much of Byrd’s music can be seen as expressing the anguish of a Catholic in hostile times, not least when he set the first four verses of Psalm 78, Deus venerunt gentes, thought to have been a response to the execution of a Catholic priest, Edmund Campion, in 1581. Both Byrd and his wife were indicted for contempt, that is, non-attendance at church, in the 1580s and 90s; he was to be gaoled in 1592 but was saved from it by Queen Elizabeth.

Tallis became the godfather of one of Byrd's sons, and Byrd witnessed Tallis’s will. He wrote a song for Tallis when he died in 1585, including the words 'Tallis is dead, and Music dies.' Byrd also taught Peter Phillips and Orlando Gibbons, and had some association with John Shepherd early in his life. In 1593 he moved to the village of Stondon Massey in Essex, 11 miles from the home of Sir John Petre, a wealthy Catholic who helped and protected Byrd. Essex was the Byrd family’s ancestral area – his forebears go back to the 14th century there. He spent the rest of his days in Stondon Massey; the Queen granted him the lease of Stondon Place, also known as Stondon Farm, in 1595.

[St Peter & St Paul, Stondon Massey]

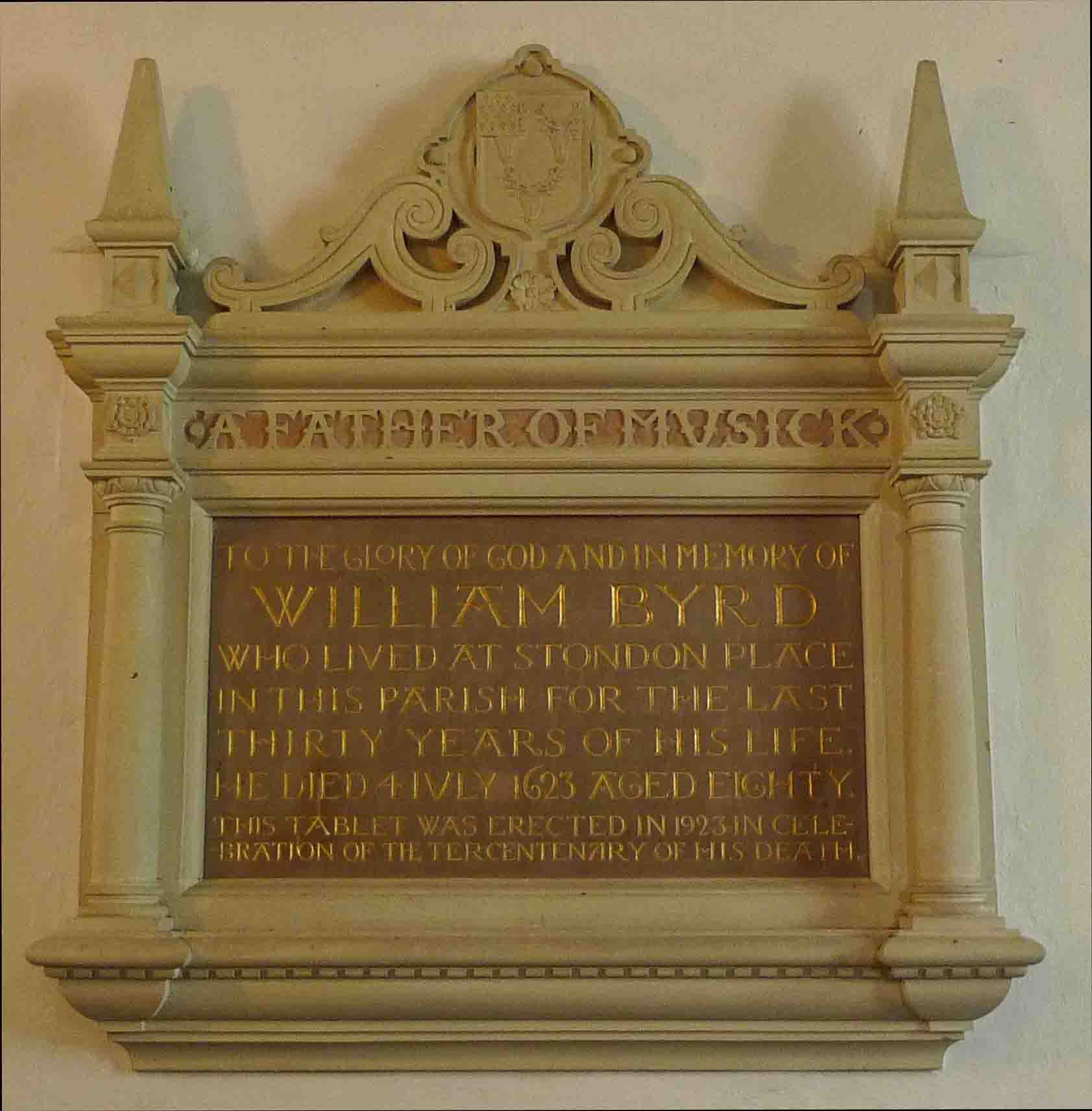

Byrd died in 1623. His will requested that he be buried next to his wife, who died 15 years before him; he was placed in an unmarked grave by the village church. The will was made 'in his 80th year' but recent studies suggest that he wrote it three years before he died, which is why his birth date is thought to be 1540. A plaque in his memory, without benefit of these studies, was placed in Stondon Massey church in 1923 (see below); there is also a memorial in Lincoln Cathedral, and a plaque at 6 Minster Yard in Lincoln, the address – but not the house – where Byrd once lived. His death was recorded in the Old Cheque Book of the Chapel Royal – “Willm̃ Bird, a ffather of Musick”.

Further reading

Brett, P. (2007) William Byrd and his Contemporaries, Berkeley/London: University of California Press

Harley, J. (1997) William Byrd, Gentleman of the Chapel Royal, London: Scolar Press

McCarthy, K. (2013) William Byrd, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Turbett, R. (1987) William Byrd: a Guide to Research, New York/London: Garland Publishing

![ [Commonly used but doubtful portrait of 1729] ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58d50854e58c62dead404c8b/1500799192714-0OGLT6KXUAHDO06441I0/image-asset.png)